A Model for Understanding Lived Expertise to Support Effective Recruitment of Peer Roles

Byrne, L. & Roennfeldt, H. (2025) A model for understanding Lived Expertise to support effective recruitment of peer roles. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 52, 482-493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-024-01424-9

What is the essential knowledge and skills derived from lived experience to inform the design of peer roles and support effective recruitment?

These concepts are embedded in our Lived-Living Experience Orientation Training. Click here to find out more.

Take Home Messages

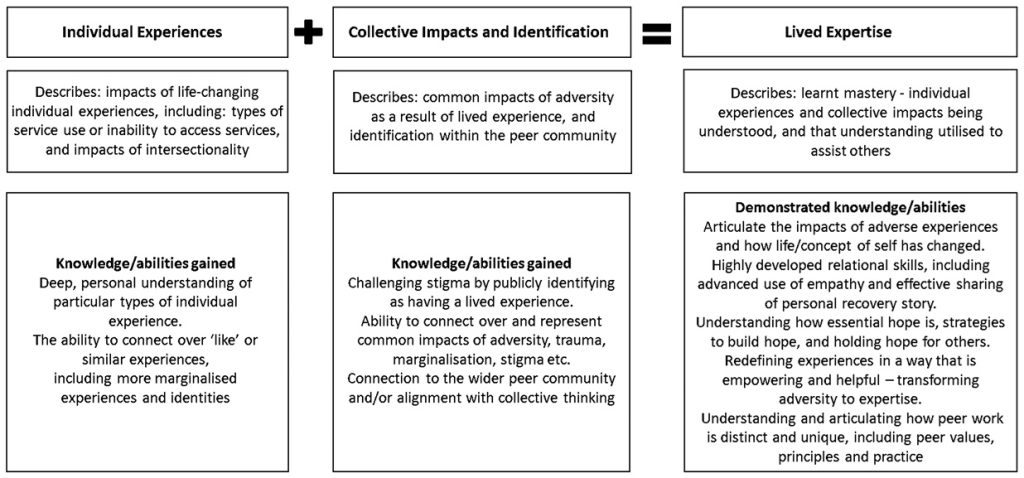

- Effective peer work is informed by three key elements: life-changing personal experiences, shared impacts of adversity, and collective peer knowledge, which together form Lived Expertise.

- Simply having lived experience is not enough. The impact of experiences, as well as the understanding gained from experiences are more important than the type or amount of experience.

- Peer work required openly identifying as a peer and identifying as part of the broader peer community

- Peer work involved the ability to share and draw from lived experience to build connection and inspire hope in others.

- Understanding common experiences of marginalisation and oppression, is often more important than having the same background or experience. However, shared culture or other identities enhances peer effectiveness.

- This model of Lived Expertise is useful to guide recruitment, training, role design, and performance evaluation to maintain authenticity, role clarity, and effective peer practice.

Aim

To explore participants’ views on the essential knowledge and skills derived from lived experience to inform the design of peer roles and support effective recruitment.

Why is this Research Important?

Peer roles have increased within mental health and alcohol and other drug services. However, there is a lack of understanding about the ‘lived experience’ necessary for success in these roles and how to recruit effectively.

Method

Participants included 132 people, including various designated Lived Experience roles, managers and colleagues in other roles. Participants were employed across 5 multi-disciplinary organisations in the U.S. These organisations provided mental health, alcohol, and other drug services and had diverse funding sources and governance structures.

14 focus groups and 8 individual interviews were conducted, with separate focus groups for peers, colleagues in non-designated roles, and management. Interviews and focus groups explored participants’ views on the essential knowledge and skills derived from lived experience to inform the design of peer roles and support effective recruitment.

Findings

Findings indicate essential aspects of lived experience compromise both:

- life-changing or life-shaping individual experiences (including intersectionality)

- common impacts of adverse experiences, identification as a peer, and understanding application of the collective peer thinking and values.

Together these essential aspects form Lived Experitse, a unique, experientially developed knowledge base and set of skills that can be used to benefit others.

Individual Experiences

Participants agreed personal experiences matter for peer work but thought there was no single definition of what’s needed. Participants discussed how much and what type of experience counts, including diagnosis, service use, personal traits, and identity factors like race, gender, and culture. These experiences were grouped into three areas:

- measuring experience

- life-changing impacts

- relevance

Measuring experience

Participants questioned what was “enough” lived experience for peer work. Experiences that didn’t cause major life disruption, was seen as insufficient. There were mixed views on culture as some felt shared cultural identity matters, while others prioritised willingness to learn about different cultures.

“Even if you look at the DSM or how they designate the diagnosis, they say we got to have 6 months of persistent dealing with this before we can give you the diagnosis, so how many months is it before you become a lived experience peer?” (Site 3, FG/P)

“What is lived experience, and is it a contest? Well, you were an inpatient more than I was, so you’re more qualified? Well, no, it doesn’t really work that way… actually, I shouldn’t say that so forcefully. I’m still debating that in my head if, you have to have more [time in hospital] and are more effective because you have more.” (Site 4, FG/P)

“Someone who may have recently been diagnosed, or who has not contended with a set of medication regi¬mens that they have to take or haven’t seen a therapist but are able to sort of self-regulate, choose them¬selves. Their lived experience would be very different from someone who had gone through all those things. That’s by which I say ‘peer lite’. What qualifies you to work in the peer world when you have not been in a hospital for mental health recovery?” (Site 3, FG/P)

“I don’t think you have to be from the same culture per se. I think that you have to be receptive to what the culture brings to you. You have to be willing to learn about the culture as you begin to work with the people.” (Site 1, FG/P)

Life-changing or life-shaping individual experience

Most participants agreed that there was a need for the experience to have life-changing or life-shaping impacts. However, the impact itself was considered complex and highly individualised.

Having similar life experiences were seen as important when people they would support were part of more stigmatised populations, such as forensic settings. In these situations, having similar experiences made peers seem better able to understand and help others effectively.

“Yeah, I see this as the criteria [for employment in peer roles], I guess… It’s like being able to attest to a life-altering experience, ‘What I went through has changed me. I’m not the same person that I initially was.” (Site 4, FG/P).

“We talked about how we have been impacted. In what ways has it impacted your life?’ It doesn’t necessar¬ily mean you have to have been in a state hospital or again; it’s not about trying to win the ‘most oppressed status.’ It’s… the complex kind of collection of things.” (Site 3, INT/M)

“I think that people that have been in state facilities and been hospitalized have a different experience and have a different set of knowledge. Still, it doesn’t make people that have not had that experience any less effective, just… maybe effective in different situations.” (Site 5, FG/P)

“There’s something really powerful in talking to somebody that has gone through the things you’ve gone through” (Site 1, FG/P).

Collective Impacts and Identification

Besides their own personal experiences, peer workers’ understanding was also seen to be shaped by shared understandings and shared identity within the broader peer community. This includes understanding the common effects of discrimination, oppression, exclusion, or social isolation. Peer workers can openly share these experiences to challenge attitudes, stigma, and discrimination.

Common impacts of adverse experiences

Peer participants generally agreed that understanding common experiences of adversity and knowing how to navigate these was key to peer work. Many felt this was more important than having similar experiences, culture, or background.

“Because you understand the adversity and working through that adversity, and so I think that’s the one common thread, that’s key – is that we see people, we’ve struggled, we know what it’s like to struggle… no matter what type that comes in the form of, I think that’s what makes us [peers] valuable.” (Site 5 FG/P)

“I don’t have to have the same background as you have, and you can still come together and work towards some common goals. So, our world view, our fam¬ily of origin, our trauma history doesn’t have to be the same, we just have to be able to acknowledge and respect that the person has what they went through.” (Site 1, FG/P)

Collective identification

Across all groups, participants agreed that openly identifying as someone with lived experience is central to effective peer work and helps challenge stigma. Identifying as part of the collective peer movement strengthens connection for peer workers and builds shared understanding. For peers in management roles, identifying as part of the wider peer community helps understand the history and uniqueness of peer roles. Identifying as a peer was also seen as a way to reclaim and define one’s own experiences.

“Not everybody with a lived experience for being a peer can do it or is going to want to do it…For what¬ever reason, they stay within the stigma, and they’re not going to share their story, or they don’t know how to share their story” (Site 4, FG/P).

“What do people know about the history of the [peer] movement? What do people know about how it’s dis¬tinct – how peer support has come to be, how it’s dis¬tinguished from regular direct service delivery…Do you identify as part of this [peer] community, and then in what ways have you been impacted by your experi¬ences, either internally or then through the system and society?” (Site 3, INT/PM)

“I think it is a reclamation; define it on your own terms… language creates reality, and make sure that the reality that I create is one that’s empowering and not medically informed.” (Site 3, FG/P)

Lived Expertise

Besides Lived expertise is the knowledge gained from personal experiences and understanding gained from common experiences of adversity, which is turned into skills to help others. It included two main ideas:

- learning from experience

- turning adversity into expertise

Learning from experience

Participants agreed that peer work requires specific skills, including being open and sharing aspects of lived experience to build connection and show empathy. Peers were seen as sharing experiences of recovery to inspire hope and help others move from hopelessness to hope was also seen as essential.

“Unique to peers in a recovery team is that we are supposed to and allowed to share those stories. Whereas you may go see a psychiatrist who has their own story, but they can’t cross that boundary. They’re not supposed to. So, it’s the commitment to sharing my story, meeting people where they are, listening, recognizing that how these things make us feel inside may be very similar, even if the facts are different.” (Site 4, FG/P)

“Has a person ever experienced a mental health diagnosis? Have they gone through a stage in their life where they’ve had no hope, and then they’ve eventually gotten some hope? I think that’s a good question to ask during the interview process; talk to me about hope; have you ever had a time in your life where you didn’t have hope, and how did you climb out of that? Because an essential part of this job is to be able to spread hope and give hope to other people, and hold hope for them, and be able to support them through that experience.” (Site 5, FG/P)

Adversity to expertise

All groups described how the insights peers gained from their lived experiences could be turned into practical skills, to effectively support others. Peers emphasised the importance of transforming deeply challenging experiences into knowledge and abilities that are valuable and powerful. understanding. For peers in management roles, identifying as part of the wider peer community helps understand the history and uniqueness of peer roles. . Identifying as a peer was also seen as a way to reclaim and define one’s own experiences.

“The kinds of stuff coming out is quite interesting in terms of defining lived experience… lived experience becomes valuable when you realize that it can be useful. And maybe that is what validates the experience – you actually have been able to embrace it and rather than see it…like your weakness, you transform it into a strength.” (Site 4, FG/P)

“This expertise derived from lived experience was defined as learned mastery, “the opposite of learned helplessness. learned survival, learned creativity, learned mastery, how can that be something valuable and powerful and something right?” (Site 5, FG/P).

Conclusion

The lived experience needed for effective peer work includes life-changing personal experiences, shared impacts of adversity, collective identification as a peer and connection to the wider peer community. Together, these elements form Lived Expertise, the demonstrated skills and knowledge gained through lived experience that are used to effectively support others.

Simply having a lived experience is not enough for effective peer practice.

Peer workers need an understanding of the shared experiences of oppression, marginalisation and adversity along with personal and collective identity as a peer. Open and shared identification as a peer enables peers to challenge stigma.

The collective knowledge and skills of Lived Expertise support peer workers in defining and holding the fidelity of their peer discipline.

This model of Lived Expertise is useful for managers and people employing peer workers to guide recruitment, training, and role clarity, ensuring to ensure authentic and effective peer work.